The Constitutional Court of Portugal: WikiWikiup.

Brief History of the Constitutional

I – The antecedents

1. The Republican Regime

2. The New State

3. The post-revolutionary period

4. The Constitutional Commission

5. The constitutional debate of 1982

6. The passage of Law no. 28/82

II – The Constitutional Court – the first twenty-five years (1983-2008)

1. The “first collection” 1983-1989

2. The “second collection” 1989-1998

3. The “third collection” 1998-2003

4. The “fourth collection” 2003-2007

5. The “fifth collection” years 2007-2012

Nature and constitutional status of the Constitutional Court

The Constitutional Court is a true court, just like the other courts described in the Constitution, but having said that, it is more than a court — it is also a constitutional body per se. What is more, as a court, it also has some important features of its own in terms of its composition and responsibilities and the way in which it works.

As a constitutional body per se, the Constitutional Court occupies a specific position and plays a specific role in the constitutional system of political authority: it can declare that legal (particularly legislative) provisions are unconstitutional, which means that they then cease to be in effect; and it possesses responsibilities in relation to the President of the Republic, national and local referenda, political parties, political officeholders, and elections.

As a court, it shares the characteristics that apply to all the courts: it exercises sovereign power (Article 202 of the Constitution); it is independent and autonomous, and is not dependent on and does not work under or within any other body; its Justices are independent and cannot be removed; and its decisions are binding on every other authority. However, unlike the other courts, the Constitutional Court’s composition and responsibilities are laid down directly by the Constitution itself; the majority of its Justices

are appointed by the Assembly of the Republic; it enjoys administrative and financial autonomy and its own budget, which occupies a separate heading under the “general State expenses” section of the national Budget; and it settles any issues concerning the delimitation of its responsibilities itself.

In the hierarchy established by the Constitution, the Constitutional Court is the first of the courts to be mentioned (in Title V [Courts] of Part III), and thus precedes the remaining categories of court.

Under the heading ‘Categories of court’, Article 209 of the Constitution says:

“1. In addition to the Constitutional Court, there shall be the following categories of court:

a) The Supreme Court of Justice and the courts of law of first and second instance;

b) The Supreme Administrative Court and the remaining administrative and tax courts;

c) The Audit Court.

2. There may be maritime courts, arbitration tribunals and justices of the peace. ”

Although Article 210(1) says that the Supreme Court of Justice is the senior body in the hierarchy of courts of law, and Article 212(1) says that the Supreme Administrative

Court is the senior body in the hierarchy of administrative and tax courts, in the same breath they both say that this is “without prejudice to the specific responsibilities

of the Constitutional Court”.

What is more, the Constitution goes on to grant the Constitutional Court an autonomous position in Title VI, where the Court is singled out and given its own constitutional treatment as another “State authority”, on the same level as the President of the Republic, the Assembly of the Republic, and the Government, whereas the remaining courts are covered together in Title V.

Precisely because the Constitutional Court is a body that guarantees the very legal/constitutional system itself, the Constitution also takes the trouble to define its main

responsibilities (Articles 221 and 223), as well as its composition and organisation (Articles 222 and 224) —something that it does not do (or at least not to the same

extent) in relation to any other category of court.

Organisation

From the point of view of its internal organizational responsibilities, the Constitutional Court must appoint its own President and Vice-President, draw up the internal regulations needed for it to work properly, approve its annual budget proposal, decide the schedule of its ordinary sessions at the beginning of each year, and fulfill any other responsibilities that the law may lay upon it (Article 36 of the LTC).

The Justices of the Constitutional Court elect their own President and Vice-President by secret ballot, without prior discussion or debate. If there are no existing President and Vice-President, the session is chaired by the oldest Justice and the secretary’s role is performed by the youngest one. For a President to be elected he must receive at least 9 votes, while the Vice-President must receive at least 8 (Articles 37 and 38 of the LTC).

The President performs various kinds of function: he represents the Court and is responsible for its relations with other public bodies and authorities; he receives both nominations and declarations of relinquishment of candidature for President of the Republic, and chairs the assemblies that determine the result of the elections for the Presidency and the European Parliament; he chairs the sessions of the Court, convenes extraordinary sessions, directs the Court’s proceedings, and determines the results of votes; he presides over the distribution of cases, signs correspondence, orders the issue of certificates, and organizes and posts the table of appeals and cases that are ready to be heard during each session, when he must give priority to those referred to in Article 43(3) and (5), as well as to those in which personal rights, freedoms and guarantees are at stake; each year he organizes the shift system under which hearings are maintained during the Justices’ holidays (after first consulting his colleagues in conference); he superintends the Court’s management and administration, as well as its secretarial and support services; he appoints and installs the Court’s staff and holds disciplinary authority over them (Article 39 of the LTC); and lastly, he fulfils any other responsibilities which may be placed upon him by law or be delegated to him by the Court.

The Vice-President stands in for the President when the latter is absent or is ineligible to perform his functions, he engages in such other official acts as the President may delegate to him, and he assists the President in the performance of his functions, particularly by presiding over one of the sections to which the President does not belong [Article 39(2) of the LTC].

Under its internal regulatory powers the Court has already instituted various regulations designed to ensure that its work goes smoothly. Some of the most important include those concerning the procedures of the plenary session and the individual sections, the notification and publication of decisions, and the use of the Court’s library and bibliographical and jurisprudential archive.

The Court’s own autonomous financial and budget system is laid down by Articles 47-A et sequitur of the LTC.

The Constitutional Court’s Administrative Board is made up of the President, two Justices, the Secretary-General of the Court, and the head of the correspondence and accounts section. Its functions particularly include current financial management and drawing up the draft budget (for approval by the Court, submission to the Government, and then forwarding to the Assembly of the Republic (Article 47-A of the LTC).

The organization of the Constitutional Court’s staff is laid down by Executive Law no. 545/99 of 14 December 1999. The staff is composed of the Secretary-General, the judicial secretariat and the support services.

With the exception of the different Offices, the staff of the Constitutional Court comes under the direction of the Secretary-General, who is in turn superintended by the President of the Court.

How the Court Works

The judicial secretariat, which is headed by a clerk of the court who also manages the central section, comprises the latter and four case sections (headed by legal clerks).

The support services include the President’s Office (with assistants and secretaries under a Head of Office), the Vice-President’s Office, the Justices’ Office, the Public Prosecutors’ Office (with assistants and secretaries), the Documentary Support and Legal Information Unit (responsible for organizing the library and jurisprudence and for publishing the Court’s decisions), and the IT Centre (responsible for planning and managing the Court’s computer systems).

Law no. 19/2003 of 20 June 2003 — Law of Financing of Political Parties — created the Political Accounts and Financing Entity (ECFP), an independent body that works with the Constitutional Court providing technical assistance in its assessment and monitoring of the accounts of political parties and election campaigns. This Entity was regulated by the Organizational Law no 2/2005 of 10 January.

The Constitutional Court sits in plenary sessions or in sections [Article 40(1) of the LTC], depending on the nature of the subject matter on which it is called to rule.

Appeals and objections in cases involving the specific verification of constitutionality and legality are heard by sections (except when the President decides that the case should be heard in plenary session because this is necessary in order to avoid conflicting jurisprudence, or when the nature of the issue at stake justifies it — Article 79-A of the LTC), as are cases involving candidatures for election to the Presidency of the Republic (Article 93 of the LTC). All other decisions are handed down in plenary.

There are three sections. They are not specialized and each of them is made up of the President or Vice-President and four more Justices. The Court decides who will belong to each section at the beginning of each judicial year (Article 41 of the LTC).

As a rule the Court sits in ordinary session every week. The frequency of these sessions is laid down by the internal regulations and their exact schedule is worked out at the beginning of each judicial year [Article 36d of the LTC].

Extraordinary sessions are convened by the President, either on his own initiative, or at the request of the majority of all the Justices in full exercise of their office.

Neither the Plenary nor the sections can sit unless the majority of all the applicable Justices in full exercise of their office are present. Decisions are taken by majority vote of the Justices present (although Article 42 of the LTC does not expressly say so, the Court’s understanding is that the need for a majority applies to both the decision itself and its grounds).

Each Justice has one vote, and the President — or the Vice- President, when he is standing in for the President — has a casting vote. In other words, if the vote is tied, the President’s

vote is decisive. Justices who find themselves in a minority are entitled to issue a dissenting statement [Article 42(3) and (4) of the LTC].

Once it has been admitted to the Court, each case is assigned by ballot to a rapporteur (Articles 49 and 50 of the LTC). He then resolves all the related issues that do not require the intervention of all the Justices involved (Articles 78-A and 78-B of the LTC), and draws up a memorandum or draft ruling containing the list of issues on which the Court is called to rule [Articles 58(2), 65(1), 67, 78-B(1) and 100(3) of the LTC].

The Public Prosecutors’ Office is represented at the Constitutional Court by the Attorney-General, who may delegate his functions to the Deputy Attorney-General or to Assistant Attorneys-General (Article 44 of the LTC).

The Seat of the Court also houses the assemblies that determine the overall results of national referenda and the elections of President of the Republic and Members of the

European Parliament.

In cases concerning the abstract, non-preventive monitoring of the constitutionality and legality of legal rules, and appeals against judicial decisions, the Constitutional Court is subject to the general system governing judicial vacations. There are no vacations in relation to other cases [Article 43(1) and (2) of the LTC]. The individual Justices’ holidays are decided in such a way as to ensure that there is always a quorum for plenary sessions and for each of the Court’s sections [Article 43(6) of the LTC]. Nor does the secretariat close for judicial vacations [Article 43(7) of the LTC].

Publicising the Court’s decisions

The Court’s sessions are not held in public, except when decisions are read and in the exceptional cases involving the exercise of the responsibilities laid down by Articles 9f and 10 of the LTC.

The Court’s decisions are notified to the parties in writing and are posted in the atrium of the building as soon as the session in question ends. They are also given to the press and to

any interested party who asks for them. Decisions that declare the unconstitutionality or illegality of a legal rule are registered in a special book, and a copy, which must be authenticated by the secretary, is filed in the Court archive (Article 81 of the LTC).

In addition, the most important of the Constitutional Court’s decisions are published in the Diário da República. The Constitution requires any decision which possesses generally binding force to be published in this way [Article 119(1)g].

Amongst other things, all decisions that declare the unconstitutionality or illegality of any legal rule or the existence of any unconstitutionality by omission, or that assess the constitutionality and legality of draft referenda, must be published in Series I of the Diário da República (Article 33 of Law no. 15-A/98 of 3 April 1998).

The other decisions are published in Series II, except those that are merely interlocutory or simply repetitive of other, earlier ones, when publication is not necessary [Article 3(2) of the LTC]. The Court’s decisions on political parties’ annual accounts are also published in Series II [Article 13(3) of Law no. 56/98 of 18 August 1998].

Constitutional Court decisions on the registration of political parties and their articles of association must also be published in the Diário da República [Article 16(1) of Organizational Law no. 2/2003 of 22 August 2003].

The Court also organizes and publishes an annual collection of those of its decisions that are of academic interest, more than sixty volumes of which have already appeared under the title Acórdãos do Tribunal Constitucional.

The Court also publicizes its jurisprudence on its website (www.tribunalconstitucional.pt), and those of its decisions that have transited in rem judicatam can be consulted at the Court’s Seat.

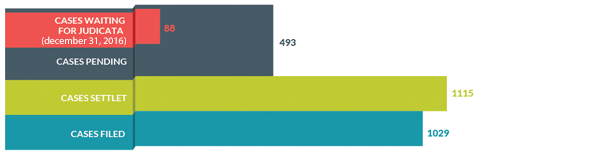

Case load 2016

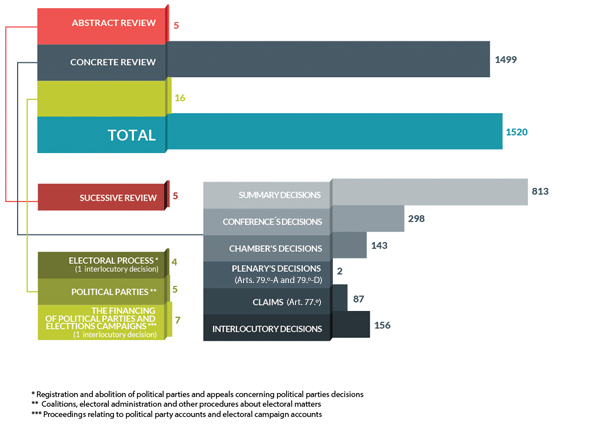

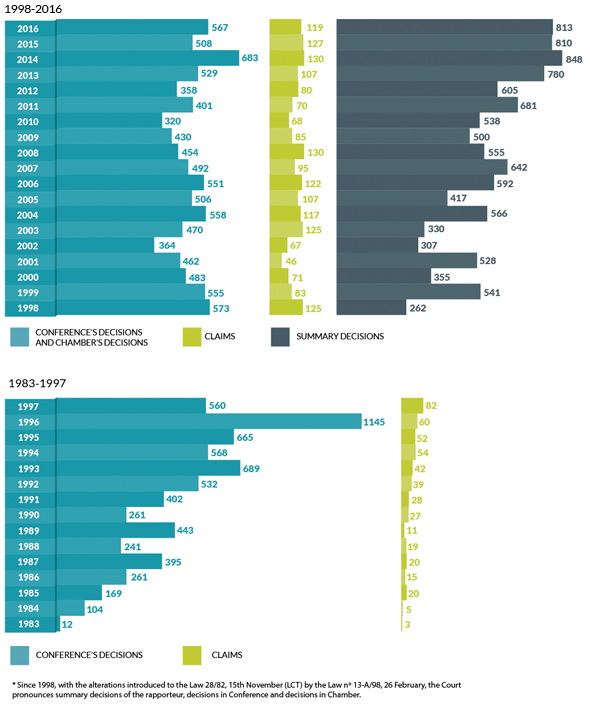

Rulings and Decisions 2016

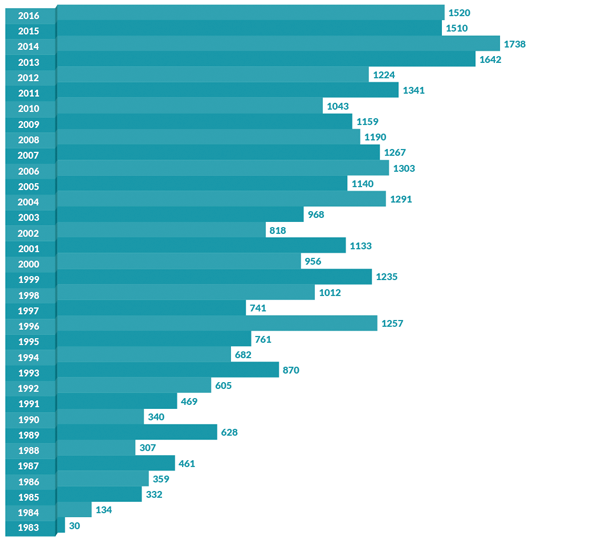

Rulings and Decisions of the Constitutional Court – 1983-2016

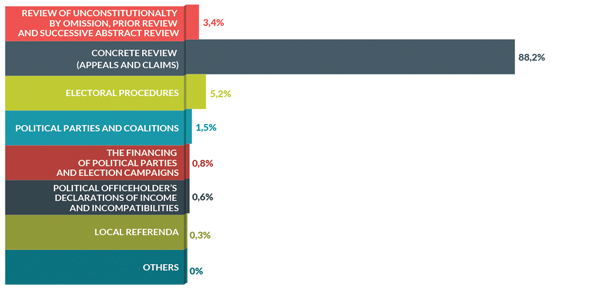

Rulings of the Constitutional Court by type 1983 – 2016

(values in percentage)

Concrete Review *

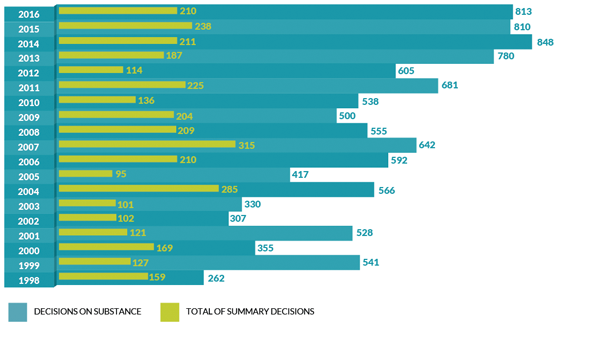

Summary Decisions 1998 – 2016